Behavioral Bias: The Slayer of Alpha

We’ve been told by colleagues that this is a curious primary objective for a new asset management firm, versus something more direct like performance and market analysis. That bewilderment only fortifies our belief that behavioral bias is a persistent but all too often silent killer of investment returns. It terrorizes not only managers, but investors in those managers. Let’s unpack both:

Investor Behavioral Bias

As a thought experiment, imagine you have decided to invest with a very secretive manager. The investment decision was underwritten by your extensive meetings with the manager, her sterling pedigree and impressive three year track record. The manager refuses to provide transparency into her holdings or proprietary risk models (beyond vague generalities / anecdotes) because it is sensitive information. What happens when performance hits a rough patch?

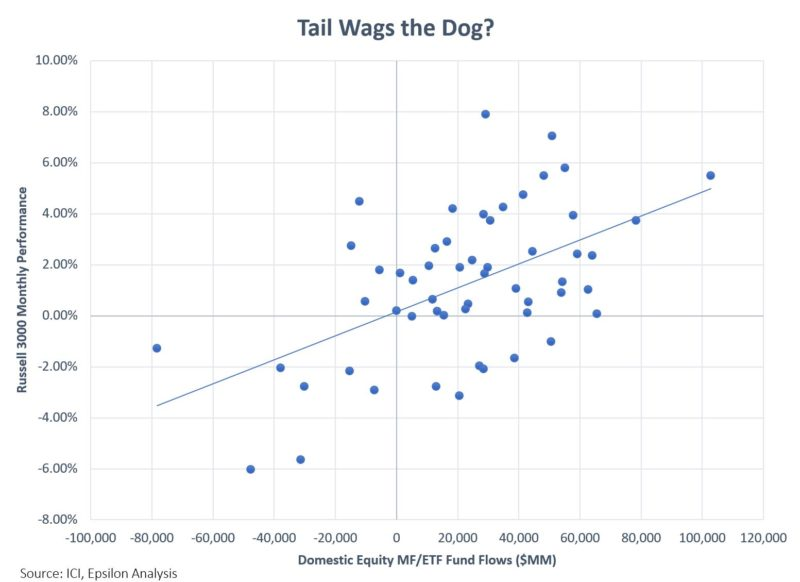

Chances are you, as the investor, are more likely to redeem at signs of trouble with a non-transparent manager. The reason is the Principal/Agent Problem is exacerbated by the lack of transparency. When humans cannot understand what is happening, they will revert to a stress response. Academic studies prove this to be the case, and the results are startling: the impact of investor timing (namely buying highs and selling lows) in underlying managers is twice as deleterious as the impact of management fees on performance1. While we cannot rewire human emotion that likely evolved out of our need to survive prehistory, we can provide incentives to break away from irrational decision making. We do this by demonstrating clearly that our investments are entirely process driven, and giving our investors perfect transparency into what they own. If this is the case, our performance is tied to the process, not to whim or reaction.

Manager Behavioral Bias

We were recently speaking to a hedge fund manager about a persistent frustration with his analysts. The conversation went something like this:

Us: What is the most common response when an analyst’s starter position goes 20% against him/her?

HFM: They say “the idea is 20% better” about 90% of the time.

Us: How often is that the case?

HFM: Maybe 10% of the time…

This is just one of many examples of an agency bias: analyst pitches idea to PM, PM puts it in the book, idea goes against them, then the analyst is in a pickle. Admit failure and risk your job, admit uncertainty and look unqualified, double down and hope to cost average your way into the green. Door #3 sounds like a panacea when your career is on the line. These are highly trained, highly competitive people who don’t like admitting failure of uncertainty, even though investing is fundamentally a Bayesian exercise of discounting potential unknown outcomes.

Other examples of manager biases include availability heuristics and sunk cost fallacies. These metastasize because of hubris: overtrading, clinging on to losers, over-riding stop-losses, making exceptions. Hubris is a hard characteristic to overcome; outside of being a robot or stoic, we believe in obviating the need by having all investment decisions handled through a systematic process.

Why It Matters

If we can start with the intention of controlling for investor biases as well as our own, we give ourselves a greater probability of driving success, not only for our firm but for our investors. We take the responsibility seriously, hence why it is foundational to our thinking.

1 – See:

- Brian R. Wimmer, Daniel W. Wallick, and David C. Pakula, “Quantifying the Impact of Chasing Performance,” Vanguard Research Note, July 2014.

- Geoffrey Friesen, Travis Sapp, “Mutual fund flows and investor returns: An empirical examination of fund investor timing ability”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Sep 2007

- Ilia Dichev, “What Are Stock Investors’ Actual Historical Returns? Evidence from Dollar-Weighted Returns”, American Economic Review, Vol 97, No 1, Mar 2007

- Ilia Dichev, Gwen Yu “Higher Risk, Lower Returns: What Hedge Fund Investors Really Earn”, Journal of Financial Economics (JFE), Aug 2009

The information contained on this site was obtained from various sources that Epsilon believes to be reliable, but Epsilon does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. The information and opinions contained on this site are subject to change without notice.

Neither the information nor any opinion contained on this site constitutes an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, including any securities mentioned in any report available on this site.

The information contained on this site has been prepared and circulated for general information only and is not intended to and does not provide a recommendation with respect to any security. The information on this site does not take into account the financial position or particular needs or investment objectives of any individual or entity. Investors must make their own determinations of the appropriateness of an investment strategy and an investment in any particular securities based upon the legal, tax and accounting considerations applicable to such investors and their own investment objectives. Investors are cautioned that statements regarding future prospects may not be realized and that past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.