Unique Insights by a Unique Asset Manager – Richard Oldfield’s Simple But Not Easy

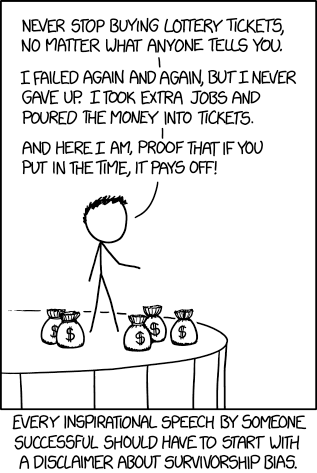

The world is awash with autobiographies from investors. The style of these works broadly ape those of famous business managers. These books introduce the world to how a successful individual overcame various adversities to build an institution with lasting brand, value, or impact. Think Shoe Dog by Phil Knight, or Made in America by Sam Walton. Both are inspirational and excellent books, but one can’t help but think of this XKCD comic after reading dozens of these:

For every Shoe Dog there are thousands of parallel stories of failure that we never hear of. Phil Knight was humble enough to constantly remind us how fortunate he was with his “bet for broke” strategy every step of the way. So what can we truly learn from them? The answer is often not much. Of course, not every book should be a polemic. A friend of mine calls these books biztainment, largely because the lessons are less important than the thrill of the ride. In that sense, they’re good beach reads.

Richard Oldfield’s pseudo-autobiographical work Simple But Not Easy is no such book (although I did enjoy reading it while traveling). Oldfield’s work isn’t the legacy piece of an investor looking to be canonized in the halls of lore. He doesn’t recount his top trades, nor his hardest, gut-wrenching investment decisions. Rather, it’s a unique insight into the mind of a value investor currently managing a global equities portfolio, who also had the experience of running a prominent family office and chairing the IC of Europe’s largest and most prominent University Endowment. It’s uncompromisingly sharp, self-deprecating, and honest. He is unapologetic about the malaise of institutional bureaucracy in investing, and shares many unique insights on the space. I’ve selected a handful that resonated with me, but implore you to give it a read (all italicized quotes are from Richard Oldfield unless otherwise specified):

Long-Termism

A baby is in an objective position to take a long-term view, but will not actually look beyond the next feeding time

I loved this point, especially in the context of our industry’s newfound fascination with behavioral economics. It is common knowledge now that having a long-term perspective is key to differentiating. We all know about Buffett’s weighing vs voting analogy. And yet, those who are the most convicted about long-termism can be dragged into short-termism due to the exogenous pressures put on them. Mindset is not enough; structure must be put in place to ensure that long-termism can thrive. It’s almost like believing in market dynamics without the rule of law / intellectual property rights. Without the foundational support, it simply cannot exist. I wrote about this previously.

The Futility of Forecasting

Managing money does not involve tremendous prescience. It requires the commonsense to be doubtful about the flawed prescience of others.

This also resonated with me, as our firm has an interesting relationship with forecasting. On one hand, we eschew it, imparting none of our views on macroeconomics into our investment process. On the other hand, our research process is about finding predictive signals in data. This is effectively forecasting! You could slice it as micro vs macro, and this dilemma occurs for just about any organization that is investing actively, but lines get blurry.

I suppose the point is less about taking risk and more about structuring risk around edges that are favorable over time. For example, if you are 55% more accurate than consensus in picking non-farm payroll beat/misses, you may be able to leverage that skill in macro trading. But it is hard to see how that creates a favorable edge that grows over time. This is because the second and third order effects of the ‘voting machine’ around an event like an NFP release are highly complex / non-stationary. In the last few years we have been in a post-modern schizophrenia where a beat could be good due to improved macroeconomic trend but bad because it could signal tightening of accommodative monetary policy. Good luck with that.

However, if you are 55% more accurate than consensus in picking stocks, you will generate a meaningful outperformance over time, as long as you manage your portfolio and risk prudently. It’s not only a function of law of large numbers; it’s a function of the favorable carry of an equity risk premia. That carry allows one’s edge to compound over long periods of time, and can drive repeatable success.

Watching Paint Dry

The business of investment is intolerably boring for anyone exempt from an instinct for gambling – John Maynard Keynes

Oldfield is a huge advocate of divorcing oneself from the madness of crowds and its impulse to react. He singles out New York and London as two epicenters for this type of behavior. As a firm based in New York, I empathize with this view, but would defensively note that New York is a big place, and there are many blocks outside of midtown that have a completely different ethos than the frenetic information game of the in-crowd. As a firm that is sadly based on one of those midtown blocks, we often look longingly at different neighborhoods that are disconnected from the ‘it’ crowd. We don’t hang with that crowd, so we can’t provide much insight toward the rat race, but we often see organizations that get caught up in it. It’s hard to get out.

Hedge Funds

…in aggregate, hedge funds are a con

We found his views on hedge funds (a primary area of our focus) to be both interesting and a bit pessimistic. His quote above is based upon the premise that hedge funds, on average, will generate the risk-adjusted market return (he uses net-exposure as that adjustment, but it likely holds true with other forms of risk adjustment). If you believe that, then the aggregate industry extracts significant fees for market-level performance, which is a con.

But many people do not, including our firm. Our research points to an excess return generated by hedge fund managers, on aggregate. That is corroborated by other researchers who have found the same (e.g., Ibbotson et al., 2011). However (and this is a large caveat), much of that excess return can be eaten by fees, and to that end, Oldfield’s pessimism towards the compensation structure of hedge funds is something we completely agree with. He seems prescient in how the world has reacted toward hedge fund fees in the last 5 years.

Index Hugging

It is obviously better to invest in an indexed equity fund than in actively managed funds which underperform. But index funds have the serious disadvantage that they behave as lunatics.

Oldfield’s main qualm with index formulation has to do with its market-capitalization threshold. E.g., for the FTSE 100, only the top 100 qualified securities ordered by market capitalization are included in the index. If a security is falling out of favor (i.e., underperforming), index-investors are forced sellers upon its drop from the index. He cites the tech bubble of 2000 as a great example, as higher quality value stocks were being replaced by lower-quality growth technology stocks, which had a nasty impact on index investors who were whipsawed across the two when the bubble popped.

Given the book was published in 2011 and likely written a few years prior, it would be interesting to see if his thoughts have evolved, given the incessant climb of indices to the chagrin of contrarian / mean-reversion-types. It would be interesting to see if he believes this is simply an attenuated process of the late 90s, or something new.

Use of active-risk as a measurement has encouraged index-clinging.

As a contrarian, mean-reversion-espousing, value-oriented investor, it’s no wonder that he finds active risk as anathema to the investment process. He cites organizations which shift from investing on convicted beliefs to looking at how deviating from the benchmark can put the organization at risk. This is classic herd mentality. It’s in sections like this where the book truly shines. Oldfield sees through the talking points of investment managers (having been one) and unpacks the hidden forces that pervert what might have been once been pure motivations. He’s absolutely firm about his hatred towards index clinging, and investors should be too. Investors fall into the trap of managing risk locally instead of globally. This is often a function of their organizational structure and the endowment effect.

Manager Vetting

Due diligence is what you have to do to show you have been diligent

Oldfield is one for less procedure and more thinking. He eschews the rigamarole associated with due diligence, investor relations, and the incentives that lead a manager to tell a client what she wants to hear rather than what she ought to hear. One such example is his view on investment boutiques who sell their business to a larger firm. They message it as added resources, synergies, stability, etc… He sees it as a cash grab, which he doesn’t begrudge (they’re there to make money!). But he does question the treatment of existing investors in these types of organizational changes.

The same goes for style drift as a function of scale. He thinks the vetting of managers should be more about their methods of thinking, their conviction, and their unique world-view, as compared to their institutional process, empire building, or business practices.

Contrarianism

It is axiomatic in markets that the consensus, if truly universal, is overwhelmingly likely to be wrong

Oldfield talks quite a bit about contrarianism, courage, and how pari-mutuel systems (like the stock market) force one to think differently in order to outperform. In that sense, his writing echoes that of Howard Marks. And yet, his answer to the thorniest questions regarding contrarianism – such as value traps – seems to rely on one’s gut and pattern recognition. He lionizes quick decision making that isn’t driven by bureaucracy or process. He exemplifies investors such as Warren Buffett who can review a proposal and ink a deal in the matter of hours.

Speaking for ourselves, as a quantitatively focused firm, this can be challenging to internalize. While we do not believe in bureaucracy, it seems difficult to think about decision making as entirely gut driven when you are a process driven investor. With that being said, this type of unique perspective is an enriching read for all types of investors. I highly recommend you add it to your holiday list.

The information contained in this article was obtained from various sources that Epsilon Asset Management, LLC (“Epsilon”) believes to be reliable, but Epsilon does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. The information and opinions contained on this site are subject to change without notice.

Neither the information nor any opinion contained on this site constitutes an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, including any securities mentioned in any report available on this site.

The information contained on this site has been prepared and circulated for general information only and is not intended to and does not provide a recommendation with respect to any security. The information on this site does not take into account the financial position or particular needs or investment objectives of any individual or entity. Investors must make their own determinations of the appropriateness of an investment strategy and an investment in any particular securities based upon the legal, tax and accounting considerations applicable to such investors and their own investment objectives. Investors are cautioned that statements regarding future prospects may not be realized and that past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.