The Curious Case of Indexation

There has been a race to the bottom on fees for passive ETF products, which we view as a natural by-product of the commoditization of beta. Part of the fee structure in ETFs is reserved for index providers (e.g., Russell FTSE, Standard and Poors, MSCI, et al.) who license their indices to ETF providers. The ETF gets stamped as having strict rules to match a properly calibrated index exposure, giving comfort to the end consumer and obviating a lot (but not all) of the steps involved in dilligencing an investment. Index providers have been an integral part of passive ETFs and their growth. Given the shrinking of top-line fees, this line item has become a meaningful operating cost for low-fee passive ETFs.

Firms like Standard and Poors deal with the thorny question of defining a risk exposure. They grapple with the rules which dictate their index constituency. They also develop a trusted brand over many years that’s well circulated in the media and the public conscience. You used to pay SPGI for the privilege, but then came along smart beta asset growth. These products relied less on brand name indices and instead sold a factor story (e.g., value, momentum, low-beta) without as much clarity behind their rules and constitution.

Besides the interesting test-case that smart-beta posed, the rise of tax loss harvesting – which is predicated upon switching exposures through nearly identical indices – provided another reason why consolidation of a risk bucket around a single index hasn’t occurred. The bottom line is, ETF providers have grown increasingly more comfortable creating synthetically similar variants (as Matt Levine so eloquently quipped, the store brand index) to traditional index providers, thus avoiding the licensing cost. Investors apparently have a strong appetite for store brand these days.

Index creation was a pretty interesting business 5-10 years ago, when institutional investors thirsted for more complete benchmark measurement for “endowment style” portfolios. MSCI was a huge benefactor of that business, as they put a stamp on global marketable asset allocation across much of the institutional investor landscape. However, the rise of these store brand variants of ETFs has provided a huge array of datasets that investors can use to measure their relative risk; not only for top-line performance, but at the constituent level. Increasingly, people are seeing that store-brand risk roughly matches premium brand risk allocation. They’re also thinking about risk allocation on their own, rather than through an arbiter.

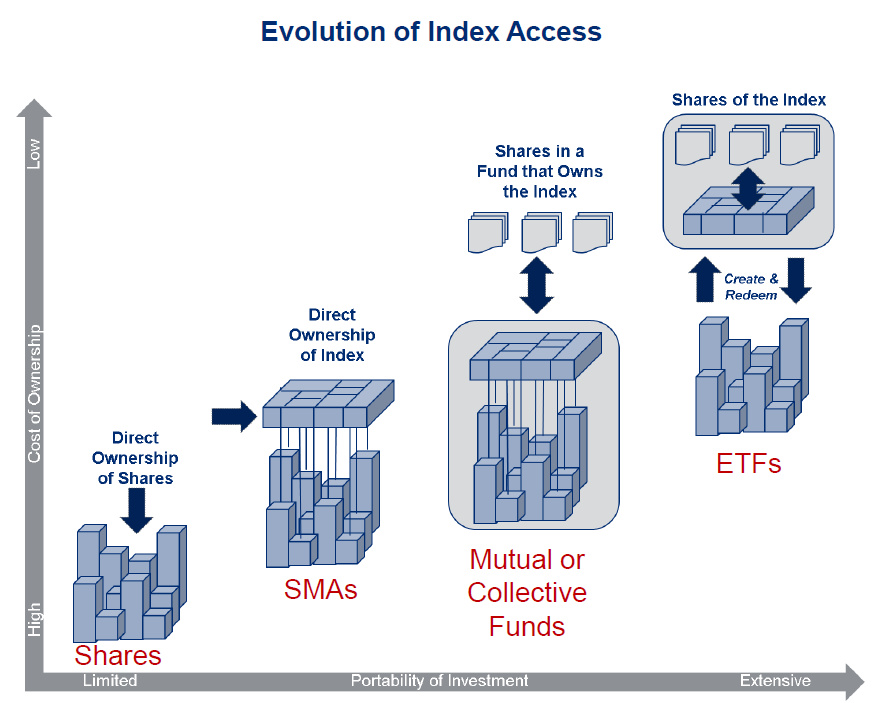

While store brands are not the official target benchmarks as consecrated by the likes of MSCI, they are undoubtedly chipping away at the concept of what a benchmark philosophically is. In effect, index companies who create massively influential benchmark decisions are being abstracted away by the investment vehicles designed to deliver their very benchmarks’ risk exposures (or pretty darn close). This is a logical by-product of the commercialization of passive risk exposures, as demonstrated in this chart by Citi:

In a sense, the ETF may eventually be more important than the index it was built to roughly represent. This is because the ETF is now the arbiter of capital flow, as the benchmark and its loose affiliation to direct index ownership and index-hugging mutual funds once was. Capital flow can influence risk factors, and ETFs have absorbed much of the capital flow from indexed mutual funds and managed accounts.

Even before the widespread adoption of ETFs, we saw hints of this conundrum in EM/FM land, with the IMI issue. Emerging market financial market indicators often included constituents that were non-investable due to the fragile or restrictive market access of certain countries to foreign investors. Market participants would argue whether the IMI was the true index. Investable indices have been winning hearts and minds as ETF financialization has made access ubiquitous.

One could argue that the rise of asset flows into the ETF almost self-referentially makes it the benchmark, official indices be damned. Imagine a world where an index deviates from the dominant ETF designed to provide access to that risk exposure. It may be over a dual-share class listing, or an emerging country’s financial market access. One would have to carefully consider the implications of using the index rather than the ETF as its benchmark. And so, the ETF has become the building blocks for asset allocation, compared to the Index Provider.

Besides determining what risks investors should be aware of, the economics of data in a world of data proliferation and increasingly more powerful data tooling is transformative. Posit: you can pay a pretty penny to MSCI to buy the constituent level data of the MSCI ACWI or MSCI EM indices, or you can do some simple data scrapping/parsing of the constituents of ETFs and synthetically calculate the respective constituent risk exposures (sectors, countries, sizes, factors, combinations).

What does all this mean? Well for one, we’re living in an increasingly fluid world where capital flow is reflexively determining asset allocation. This is especially the case with smart-beta, ESG, and liquid alternatives. Epsilon constructs “liquid alt” benchmarks to calibrate its performance with a counterpoint to simple index benchmarks. We expect this proliferation to continue downstream as access to asset allocation building blocks continues to become commoditized (e.g., robo-advisors).

Which leads me to one final philosophical point. The precision of asset allocation and optimal diversification was historically a luxury of the institutional investor who could afford to buy expensive data and tailor their investment decision to optimize asset allocation with fancy in-house quant models. The benefits and access to diversification is increasingly commoditized by the ETFization of indices and the cottage industry of products that sit on top of these ETFs. Beta continues to nibble up the value chain of asset management.

—

The information contained on this site was obtained from various sources that Epsilon believes to be reliable, but Epsilon does not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. The information and opinions contained on this site are subject to change without notice.

Neither the information nor any opinion contained on this site constitutes an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, including any securities mentioned in any report available on this site.

The information contained on this site has been prepared and circulated for general information only and is not intended to and does not provide a recommendation with respect to any security. The information on this site does not take into account the financial position or particular needs or investment objectives of any individual or entity. Investors must make their own determinations of the appropriateness of an investment strategy and an investment in any particular securities based upon the legal, tax and accounting considerations applicable to such investors and their own investment objectives. Investors are cautioned that statements regarding future prospects may not be realized and that past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.